Azadeh Pourzand: Reflections on ‘The Journey’ by Francesca Sanna

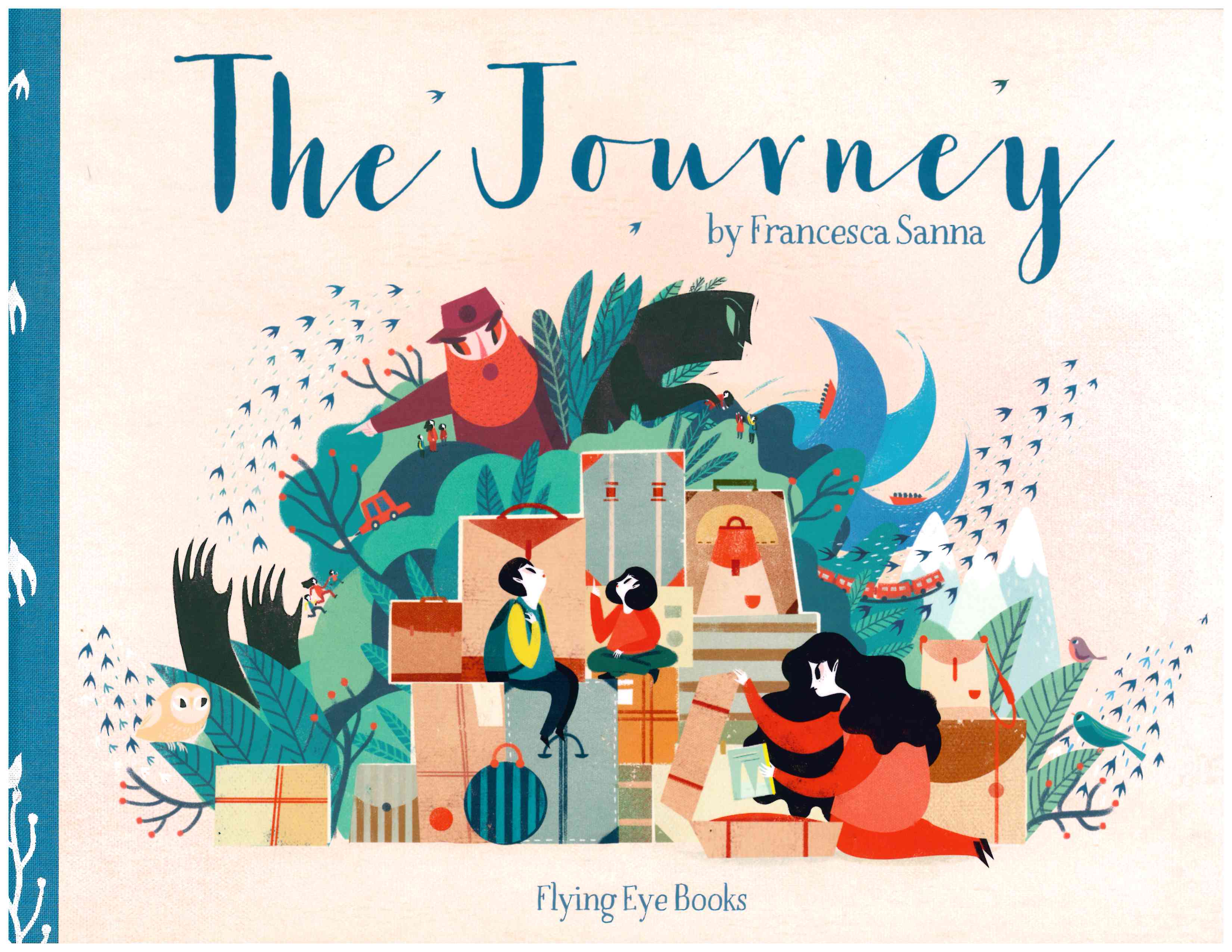

I recently received a gift in the mail from a friend. The gift is a children’s book. It came along with a short note, saying that the story reminded her of my story. The book is called The Journey by Francesca Sanna.

I started to read it right away. As I turned the pages, time stopped. I became a child asylum seeker that I once was. I recalled being pushed away from my beloved birthplace, in search of a new home somewhere safe, anywhere in the western hemisphere. I eventually found my new home in the United States, a country that I call home with love and affection. I understand that my current home is not perfect, but that it is my responsibility to contribute to its improvement.

The Journey is about the story of a family who lived a happy life somewhere by the sea, told from the perspective of one of the children of a small family. A horrific war breaks out, turning their life into a nightmare. The two children lose their father in the war, and are left only with their mother by their side. The mother ultimately decides to take the children to a safe faraway land. They set out on a difficult journey across the country and borders, facing scary guards and strangers who sometimes help and sometimes scare them. They eventually get on a boat with lots of other people, and make it to the shore after a long and difficult time at sea. They feel fortunate to reach the shore without losing each other along the way. But, that is not the end of their journey. They then get on a train. While riding the train, the child watches the birds flying away, and wonders if the birds are also migrating to a faraway place. Thinking about the long journey and all that they have left behind, the child hopes to find a new home where their story can resume once again.

The language of the book is simple, and likely comprehensible for children who are early readers. The illustrations of this book, and the tactful use of dark and bright colors throughout the journey are simply incredible. The illustrations speak to the reader with such clarity and strength. In my opinion, the illustrations serve as the child’s unfiltered perspective. However, the illustrations may at times be overwhelming for younger children without an adult around to guide them. With beautiful illustrations and simple language, this book raises awareness for adults and children, sparking important conversations about the human experience.

Francesca Sanna has courageously taken on an ambitious endeavor, by relying on interviews to come up with the plot and the illustrations of this book. As she describes, “The Journey is actually a story about many journeys, and it began with the story of two little girls I met in a refugee centre in Italy.”

I am still not brave enough to narrate my own version of The Journey. Every time I decide to write my own story, the rational adult in me suddenly turns into a lost child. I lose the ability to coherently describe what happened. I rush through the descriptions to get to the end, wanting to finish it fast. “What if I can’t manage to show how strong my mother was all along?” I think to myself. “What if readers only see me as a victim that I always hated to be? What if people think I am too melodramatic with my stories? What if they don’t believe my story? What if the readers don’t understand that my father wanted to stay and die in his country, and judge me for having left him behind to die alone? What if I sound irrelevant to those back home after all these years? What if my version of the journey turns out very different or even contradictory to what my mother and my sister have in mind?” – these thoughts and a thousand other what ifs conquer my thoughts and stop me from putting words on paper.

I think Francesca Sanna has well understood that The Journey does not end for most who lose a home and find a new one; it never ended for me. After struggling for years, I have accepted that I will always feel emotionally displaced. It took me years to realize that emotional displacement, or longing for what I left behind, is not necessarily a bad thing, and does not need a cure. I can be an American and still miss the home that I left behind. I can be an American and still try to preserve aspects of my heritage. I can also choose to entirely leave behind the heritage that represents my birthplace. This is entirely up to me, and no one can force me in either direction. Still, one thing is for sure: finding a new home does not necessarily mean forgetting about the old one.

Moreover, there are things that I cannot forget in this journey. No matter how many years pass from the first time I watched my strong mother break down and cry, not knowing how to save her child, I feel guilt-ridden and scared at the idea. Similarly, no matter how rational I have grown as an adult, I can never forget how it felt to lose the feeling of safety at home and to say goodbye to my relatives and friends for good. Twenty years later, I still try to imagine the home we left behind in great details whenever I feel anxious. The exercise calms me down. I remember where every single piece of furniture was the day that we left our home forever. I remember the title of many of the hundreds of books we had at home, the kinds of plants we kept in our apartment, the color and design of our carpets, my dolls and so much more. The new home’s caring people and opportunities do not replace the sense of security, familiarity, and family unity that political beasts took away from me as a child.

I loved the United States the moment I saw it. I felt like I was in all the dubbed movies I had watched back home. I was fortunate to feel loved and welcomed when I first arrived. Nevertheless, gradually I began to grow bitter with my surroundings in the new home. I felt as though the people in the new home, the new society, found me interesting because of my story, because of the journey. I felt as though no matter how hard I tried to transcend the journey, they only recognized me because of my story. It is as though I was not interesting enough, human enough, equal enough if it weren’t for the journey. I gradually grew detached and bored with my story. It felt redundant, and a barrier for others to see my other achievements in life. I grew tired of amusing the people of the new home with my story. I got tired of always having to answer the following question: “Where are you really from?” It is as though saying that I am from Washington DC is not satisfying enough of an answer. The people want to hear a better story, a real one, an authentic tale, and one that matches more closely with my accent and all the stereotypes out there.

Simply put, I do not think that refugees owe others a good story. In this context, reading this book triggers difficult memories and complex sentiments in me. I struggle with a sense of resistance against the story. I worry for the children in the story even after the family finds a new home beyond the pages of this book. For some reason the simplicity in the words of the book bothers me. I feel a sense of anger that we have to water down the story not to bother the readers who may not have experienced the journey. I recall the number of times people have made an oddly sad expression on their face even as I have tried to tell them a funny version of my story. I like the illustrations of the book more. They paint a more real picture of the journey than the words.

My personal experience against the watered down version of the journey aside, I think I would want to protect my child against the notion of war, displacement, state violence, loss and suffering for as long as I could. Bluntly put, I would censor the book for my child; and ironically I am an avid advocate of freedom of expression. I would read and show my child the page that captures the family’s happy life by the sea, and later their colorful journey on the train with the migrating birds flying over them.

We do not want our children to worry that they may lose their home. We also do not want them to feel amused by other children’s suffering. We want them to understand that having a safe and happy home is a privilege not to be taken for granted. We want them to understand that in today’s world, many struggle to find a safe home. Without transferring our first world guilt onto the children, we have to find creative and effective ways to invite them to take responsibility towards others.

No child owes another child her/his life story in order to feel appreciated, welcomed, or understood. The dilemma is how we can make our children aware of global challenges without solely relying on other people’s story of suffering. While I do not think there is a straightforward answers to this dilemma, I also do not feel that The Journey is meant to offer such a solution.

Lastly, it is important to read this book not as the story, rather as one of the many personal stories that aslyum seekers and refugees have generously shared with the rest of us. There may be similarity in many of these stories, but every story has its own special moments, character, colors, fears, hope, and beauty. Every child has her/his own perspective. Let us not force all these stories into one box. This book’s job is simply to remind us to think more critically and do more regarding this global trend that affects many children around the world.

I took The Journey as a gift for my little niece when I came to see her in Canada during my winter holidays. She saw the book and asked if it was for her. I found myself caught in a dilemma and told her: “Yes, this book is yours. But, it is for when you are a bit older.” She responded with discontent, “I am a big girl.” I answered softly, “You are a big girl. That’s for sure. But this is for when you become even bigger.” I quickly handed her a coloring book that I had also brought her and successfully distracted her away from The Journey. I am not yet ready to break her heart with such a real story, even if I know many children her age are currently living it.

My most favorite activity with my niece is to dance to a song with the following punch line: “I am going to Tehran, because it is the new year (Norouz) when spring with its beautiful blossoms arrive in the city.” She dances to this song with me and her mother, and chants with excitement, “I am going to Tellan (her version of Tehran)” in Persian with her adorable English accent. She loves the song, and knows that her mother was born and raised in a beautiful city with colorful springs called “Tellan.”

Her happiness in a land faraway from what used to be our home is our collective achievement after years of The Journey. Neither one of us in my family is ready to interrupt the little girl’s happiness in a land where her mother, back then a young girl, reached and settled in with much difficulty, loneliness, and hard work. When it was time to say goodbye, my niece ran towards me with a drawing in hand and said, “Were you also born in Tellan like my mom?” I said, “Yes! How did you know?” She said, “I just guessed!” Then she handed me her drawing and said, “This is for you. It is the map of the whole entire world with Canada marked up so that you do not get lost the next time you come to visit me from your own home.” It seems the little child is finding her own way to come to terms with her family’s journey. We enjoy her version of The Journey that is creatively and slowly coming together, rather than our version that comes along with too many real images and lingering feelings of loss and melancholy.

Still, Francesca Sanna’s The Journey is a masterpiece that captures so much complexity with simplicity, creativity, and clarity. We should not overburden the book with a heavy load of educational responsibility. Francesca Sanna has done her part as a concerned and empathetic citizen of the world. We should do our part, without solely relying on her version of The Journey.

Azadeh Pourzand

Guest Blogger, Co-Founder of Siamak Pourzand Foundation

Azadeh Pourzand is an international development professional with eight years of work experience including management of civil society and governance projects in the Middle East. Azadeh currently works for an organization that provides digital advocacy support to civil society actors in at-risk communities globally. Previously, she manage an extensive civil society strengthening program at IREX in Washington DC. In 2015, she was awarded a fellowship at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). Azadeh has a Master of Public Policy (MPP) from Harvard Kennedy School of Government (HKS), and a Master of Business Administration (MBA) from Nyenrode Universiteit. She received her Bachelor of Arts from Oberlin College. While at HKS, she served as the editor-in-chief of the Women’s Policy Journal. Her recent publications are focused on rule of law, human rights and the geopolitics of the Middle East. Azadeh has also co-founded Siamak Pourzand Foundation, an organization that promotes freedom of expression in Iran.